Back behind the dumpster at the old 7-Eleven on Winter Springs Boulevard in Tuscawilla there’s a pit in the ground, dug maybe five feet deep.

A used 500-gallon liquid propane tank, dark forest green, sits exposed to the air. A warped sheet of plywood covers part of the top. Nearby, chunks of broken concrete are piled up.

A yellow hose attached to the tank loops lazily in a circle, before vanishing underground. It reappears near the 7-Eleven building about 30 feet away.

The liquid propane tank – which is empty – is unpermitted. It’s roped off with red plastic tape with ‘DANGER’ emblazoned on it. Next door, toddlers play on a playground at the daycare.

Seminole County Fire Department’s Fire Marshal was called to the site Oct. 30 and issued a Stop Work Order.

“Our Fire Marshal subsequently confirmed with the City of Winter Springs that no permits had been obtained and followed up on the complaint shortly thereafter, at which time the tank was found to be installed without a permit,” wrote Doreen Overstreet, Seminole County Fire Department’s public information officer. “Based on our findings during the site visit, the property was posted with a Stop Work Order.”

The propane tank is the most visible sign of what went wrong at 898 Gary Hillery Drive, a site that was supposed to become The Clubhouse Deli.

When a liquid propane tank is put in the ground, the hose must be buried a certain depth, with a radio wire so the line can be found without digging. Above the line, a foil must be buried to alert future diggers that there’s a gas line below.

None of that was done.

Zaya Givargidze, who goes by “Z”, is the property owner. He’s giving a tour of the property, wearing jeans and a hoodie from a carwash he also owns.

Givargidze has a gray beard and an occasionally colorful Long Island accent. He doesn’t mince words: He calls the site an “abortion.”

Givargidze spent the last four months suing his tenant, Robin Neilen, for a commercial eviction to get him out of the site. Givargidze said he estimates the cost to get the property back to a condition where it can be leased to a new tenant at $300,000 to $400,000.

Givargidze is clear on where he thinks the blame lies. The city of Winter Springs first issued a stop-work order against Neilen on April 16, 2025.

“The fault here is Winter Springs and the courts. They let him do all this without a permit,” Givargidze said. “You see him doing work (afterwards)? Cuff him. They let him get away with murder.”

Neilen, the tenant, disagrees. He also puts fault with the City of Winter Springs, but for a different reason. He said it should have taken “two weeks” to get a permit to build out the 7-Eleven and reopen it as The Clubhouse Deli, an Italian deli and pizza restaurant.

“[The city] bled me out until I ran out of cash. And then everyone jumped in,” Neilen said. “It seemed like I was the carcass in the field and the vultures were trying to get a free meal.”

He said he had $100,000 to $200,000 budgeted to build out the 7-Eleven.

“The city strung me out for six months to get a permit. Now I have eight months of rent that wasn’t in my business plan,” Neilen said. “This has been the worst nightmare anybody should ever have. What I went though, no one should ever have to. I’ve lost my life savings.”

From Dominick’s to Marie’s to the Clubhouse Deli

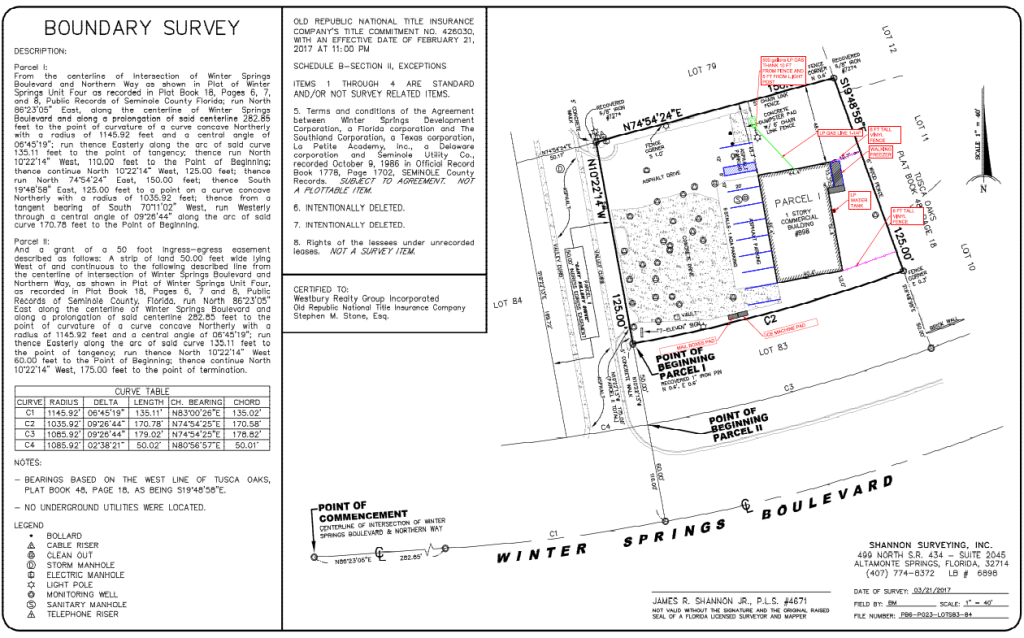

To understand the full story of what happened at the 7-Eleven at 898 Gary Hillery Drive, you have to cross the street and head to the former Dominick’s To Go restaurant, a Tuscawilla staple for decades.

Dominic Commesso, the owner of Dominick’s To Go, said he had been losing money “hand over fist.” So on Oct. 16, 2024, there was an auction for all the “furniture, fixtures and equipment” at Dominick’s.

In an interview with Oviedo Community News, Neilen said he had Commesso sign an agreement – but later lost the copy of it. Neilen said he paid Commesso in actual, physical cash.

“Cash, yes. That day, yeah, I came here and took cash and went back and gave him cash,” Neilen said. “Why would he allow me to have the business if (he) never got the money?”

Commesso tells a different story.

Commesso said he met Neilen through Ken Greenberg, a former Winter Springs City Commissioner and cofounder of The Winter Springs Community Association, which is active in local politics.

Commesso said Neilen seemed like a godsend. Neilen said he would buy the restaurant for $150,000, split over five $30,000 payments. And he would take over the lease and keep Commesso on payroll for two years as an adviser.

Neilen paid $15,000 to the auction house to stop the auction from happening. That first week, Commesso said Neilen paid him $20,000 – $10,000 short.

And that was the only payment he got from Neilen, he says. But, Commesso added, he never got the deal in writing.

“That was my mistake,” Commesso said. “Because he was recommended by Ken Greenberg and because I’m a handshake kind of guy.”

When he didn’t get the rest of the money for the deal, Commesso had Neilen trespassed from the restaurant, with police barring him from entering. Neilen sued, saying he had paid for the equipment.

Neilen, through two of his companies, said in court filings that he spent $100,000 for all the equipment inside Dominick’s, plus $15,000 to the auction house to cancel the public auction that was meant to sell off the equipment. That amount was in dispute, though, with the auction house submitting a letter saying that Neilen never paid the $100,000 through them and that a receipt they issued was because they were “deceived” by Neilen.

Ultimately, though, the courts sided with Neilen on March 16, 2025.

“The court found plaintiff Neilen’s testimony credible and reasonably concludes that (Commesso) and (Neilen) entered into an agreement whereby (Neilen) would take over the operations on the next business day and would continue to employ (Commesso), and that (Neilen) purchased the equipment and paid outstanding and overdue restaurant bills in an effort to prevent the restaurant from closing,” the judge wrote. “(Neilen) reasonably expected a return on his investment. … As a result, the court finds (Neilen) purchased the equipment and had a right to possess the same. By trespassing (Nelien), (Commesso) wrongfully detained property.”

Neilen was able to strip Dominick’s of its assets: Everything from pizza ovens to jars of sauce and frozen meat and homemade Limoncello steeping.

Court documents showing the assets at Dominick’s that Neilen received.

Neilen spent weeks moving everything into a shipping container for storage on site. To this day, the former Dominick’s site sits empty.

And then Neilen signed a lease to move all that equipment to open The Clubhouse Deli at the old 7-Eleven site.

‘The codes are written in blood’

On March 15, 2025, Robin Neilen signed a lease for the property at 898 Gary Hillery Drive.

The old 7-Eleven off of Winter Springs Boulevard in Tuskawilla was going to cost $7,500 per month in rent, according to court filings.

But Givargidze said he was worried about renting to Neilen, who had been named in at least 19 lawsuits in Orange, Osceola and Seminole counties, going as far back as 1990. But Givargidze knew the community wanted a restaurant of some kind, and he liked the concept.

So he required four months worth of rent upfront as the security deposit – $30,000. Neilen then paid on June 1 – the actual rent, but not enough to cover the insurance and sales tax that was also due with the rent. That was the last payment from Neilen to Givargidze, according to court documents.

By Sept. 1, Westbury Realty Group sent Neilen an invoice for overdue rent and insurance totaling $34,927.

Giving a tour of the 7-Eleven, Givargidze said before Neilen took over, the building had been empty, but was functional. It had working bathrooms. But as he walks through the building, it’s full of holes.

Currently, the floor of the 7-Eleven on the inside is dug up, with waist-high dirt in piles and pipes exposed in the ground. Pink insulation hangs from the drop ceilings. There are deli cases on wheels, acquired from other auctions, and racks of equipment and tools.

Outside, there are stainless steel sinks with standing water from a recent rain. Opening the shipping container up, there are old soda fountains and stacks of frying pans. The air inside smells stale.

At one point, neighbors complained about the smell. When the power was cut, more than 800 pounds of frozen meat spoiled – meat that was leftover from Dominick’s restaurant.

“Everybody robs him (Neilen),” Givargidze said. “But he’s the common denominator. … The guy’s just a deadbeat. You got million dollar homes across the street looking at this crap.”

Givargidze said the last time he saw Neilen was after he had been served with eviction paperwork. Neilen was prepping to paint and talking about working out a deal so he could open up.

He should have been moving his equipment out, Givargidze said.

“This he did on the Sunday before he got evicted,” Givargidze said, pointing to the speakers. “There’s no way I’m starting over with this moron. I’d just as soon leave it empty.”

James “Jay” Miller was one of the contractors Neilen used on the Clubhouse Deli project. Miller said he heard about Neilen’s reputation, and required payment ahead of time to do plumbing work, so Neilen does not owe him money.

Neilen sued Miller’s company, arguing that he paid $7,000 for work on the bathroom that didn’t pass inspection. The case was dismissed when Neilen failed to appear for a hearing.

Miller said he was worried about the propane tank, the fire suppression system and the commercial cooking ventilation hood hung inside the 7-Eleven. Miller said Winter Springs needs to update its codes and its process for code enforcement.

The codes are there for a reason, Miller said. The liquid propane tank buried in the ground is essentially a “bomb” buried in the yard if there’s a fire. If there’s a grease fire and the fire suppression system doesn’t work properly, employees or people in the restaurant could be killed in a fire.

“The codes are written in blood,” Miller said. “That’s literally what has to happen for codes to change.”

Subcontractors flood a Winter Springs meeting

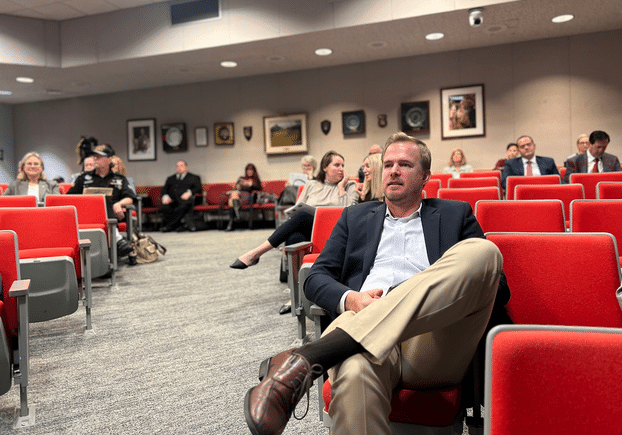

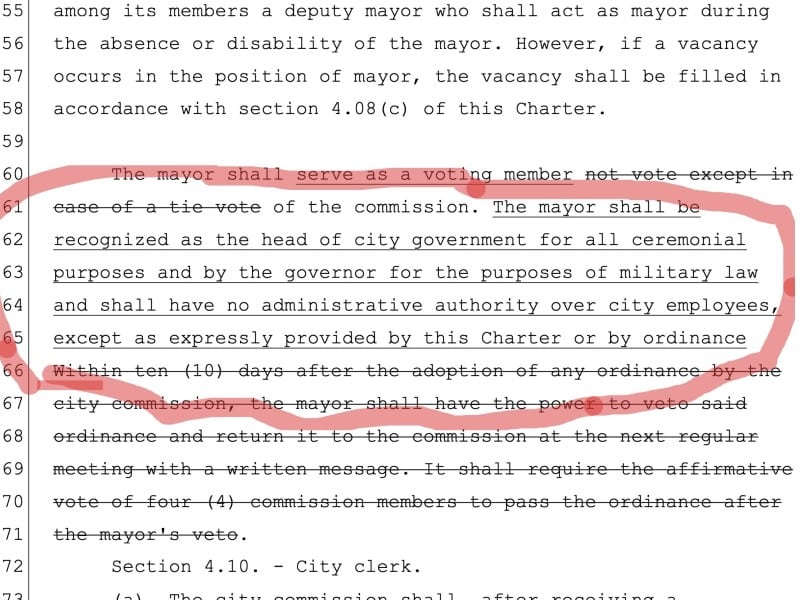

On Oct. 13, Commissioner Paul Diaz had requested the Winter Springs City Commission have a discussion about “concerns surrounding a project” at the 7-Eleven site.

The discussion never happened. But two subcontractors and Givargidze came and told commissioners that Neilen owed them money. Miller also detailed his concerns about the site to city commissioners.

Jeff Cuddy is the owner and operator of Metal Mayhem Fabrication. Cuddy said Neilen owed him $8,500 for two jobs, including work at the 7-Eleven, and was never paid.

Cuddy said he has two small children. He said losing $8,500 happened around the time he had birthday parties planned.

“It’s very hard. I was able to get them some birthday presents,” Cuddy said. “I think $8,500 to a lot of people in America is a great deal of money.”

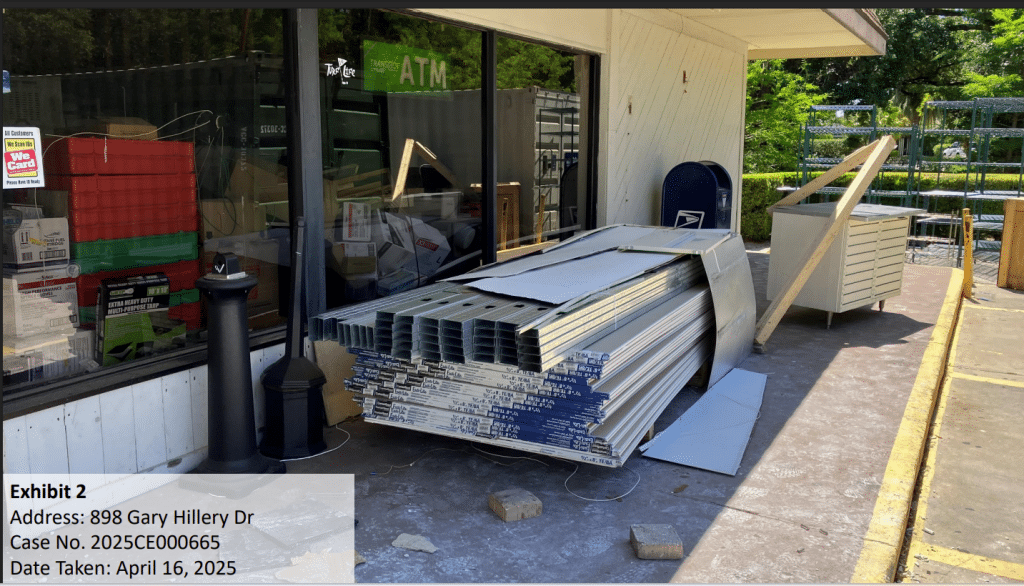

This wasn’t the first time the old 7-Eleven came up in official city records. Code enforcement was first called to the 7-Eleven on April 14, finding work being done without a permit.

“[Neilen] claimed the work being done was not permit-required based on the information given to him by an unnamed employee of the city,” the inspector wrote. “I assured Mr. [Neilen] the scope of work at present requires a permit and an authorized letter from the property owner.”

On April 16, a “stop work order” was issued and taped to the front of the 7-Eleven. On June 3, code enforcement again found work being done without a permit. So code enforcement was called.

But the code enforcement action wasn’t against Neilen directly as the tenant. Instead it affected Givargidze as the property’s owner. He was brought to the Code Enforcement Board on July 22, 2025.

Code Enforcement Officer Chris Elbon had been at the 7-Eleven in April and June and saw work being done after the stop work order was first issued.

“We could potentially start imposing fines of $250 per day to get some voluntary compliance out of that,” Elbon said to the Code Enforcement Board members.

Still, some board members questioned why the city wasn’t doing more.

“What’s the purpose of the stop work order?” Member Maurice Kaprow asked. “I don’t understand why we post stop work orders when we do nothing with them when they’re violated?”

“I wouldn’t be able to answer that right now,” Elbon replied.

Givargidze was found by the Winter Springs Code Enforcement Board to have been in violation of work without a permit at the July meeting. But work still continued after that, with Elbon noting yet another violation on Sept. 23.

A construction permit was finally issued for the 7-Eleven on Oct. 7. But by that point, Neilen was already in the eviction process.

Winter Springs spokesman Matt Reeser said it’s not on the city to monitor a site for compliance.

“It’s not on the city to stand by and say ‘we’re gonna watch you,’” Reeser said. “Yes, in a way there’s nothing to stop an applicant from doing work. But what are the consequences? You can have your license revoked, you get no license of occupancy. The penalties start to increase.”

“There’s only so much we can do if someone’s not following the rules,” Reeser added.

What to do when building officials get the ‘proverbial finger’

Phil Kersey, the chief building official for Seminole County, was not involved in the Winter Springs case.

He said cases like this can be difficult. But they’re more common than you would think.

“If someone wants to give you the proverbial finger, it’s a lot of burden for a municipality to deal with,” said Phil Kersey, the chief building official for Seminole County.

Historically, he said, Florida passed a statewide minimum building code standard after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 reportedly destroyed more than 25,000 homes and was directly attributable to 26 deaths.

Kersey has worked in code enforcement in smaller jurisdictions like Maitland and Longwood, as well as being the head of code enforcement in Seminole County. Building officials are, technically, vested officials of the clerk of the court and have arresting authority.

“It’s not as cut and dry as it sounds,” Kersey said. “Tenants have rights. Property owners have rights.”

There is another tool in the arsenal though, Kersey said. Building officials can have the power, water and utilities turned off to a building if there’s a threat.

No power, for example, makes it harder to continue doing work at a site without permits.

“It’s the sweating out option,” Kersey said. “The last thing anyone wants to do is forcefully take someone out of a building. But it’s been done.”

Neilen speaks: ‘I’m not going to defend anymore’

The house Robin Neilen lives in at 1033 Northern Way has shredded remnants of blue tarps on the roof, which leaks in four spots when it rains.

In the driveway, there are two Sanford Electric Company vans parked outside, the tags expired. A fountain in the circular driveway is dry, clogged with leaves.

Neilen wore a black, short-sleeved shirt with an embroidered marlin poking out of the front pocket. His jeans had white paint splattered on them.

The home is littered with the remnants of planned businesses: digital scales to weigh out meat for the deli, an ice cream machine and computers and monitors.

Inside the home’s high-vaulted ceilings, Neilen points to plastic crates and cardboard boxes of liquor and wine in his living room. In his garage, there are even more cardboard boxes of Bombay dry gin, Grand Marnier and Macalan 12-year scotch – many of the bottles are open with pour spouts.

It was all going to be used in The Clubhouse Deli and Marie’s Ristorante & Pizza Inc. before that.

‘I got damaged by the city’

“What I’ve learned is the more that I defend, the more I look guilty, and I’m not going to defend anymore,” Neilen said. “You believe what you want to believe. … I got damaged by the city.”

Neilen said he was “targeted” by the city. It took months to get a permit, he said, which delayed him from opening.

Neilen said it would still only take “two weeks” to open as a convenience store, and another month to finish the restaurant side. That’s despite the floor being ripped up.

“That part was the restaurant side, and that would take a month to finish,” Neilen said. “And I agree with you on that side, yes, that’s a month. But [the city of Winter Springs] was gonna allow me to block it off and work on that (restaurant) side while we were running the convenience store.”

He said the city wouldn’t tell him specifically why his permit applications were being rejected. He said the city was also requiring him to have bathrooms that were now compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was costly.

He was finally able to get a meeting with the building department, the city manager and his contractors after he said Ken Greenberg, again, got involved.

When asked what he was worried people would get wrong about his story, Neilen opened up about his health issues. He lifts his shirt up, revealing a long scar along his stomach, maybe half and inch thick. He said in 2003, he was given six months to live.

“Multiple surgeries from cancer and Crohn’s (disease). I had 18 feet of my bowel removed,” Neilen said. “So I ended up, next 10 years, not being able to work.”

Neilen said that depleted his finances. He said he was in and out of the hospital in 2025 as well.

“And I got sick again during this time, so I’ve been struggling, trying to get my health back,” Neilen said. “I was in the hospital for six months (in 2025)…. Nobody knew.”

According to emails obtained by Oviedo Community News, Greenberg got involved on Neilen’s behalf.

In an interview, Greenberg said the city of Winter Springs had an inspector that had a “personal vendetta” against Neilen.

“They jacked him around,” Greenberg said. “They charged him fees that shouldn’t have been charged. It’s embarrassing. I wouldn’t develop a doggy door in this city at this point.”

Greenberg said he knew Neilen through Republican political circles.

“Robin’s a good guy,” Greenberg said.

What’s next for the 7-Eleven and Robin Neilen

So what’s next for the 7-Eleven site?

Givargidze has gotten an eviction order for Neilen, but the judge also wrote an order letting Neilen come get his equipment out of the site. That hearing happened in December, and now Givargidze is appealing that decision.

It could take months to get the building ready to be leased again.

“Everything he did here, he did to himself,” Givargidze said. “Robin had the right ideas, but he wasn’t the right person.”

Does he plan on suing Neilen? Givargidze laughs at that.

“I’d be the 80th person in line,” Givargidze said. “I can’t even get my own property back from him. It doesn’t make (expletive deleted) sense.”

Want to contact your Winter Springs elected leaders and weigh in on this topic? Find their contact information here. Have a news tip or opinion to share with OCN? Do that here.

Abe Aboraya is a Report for America corps member

Sorry for the interruption but please take 1 minute to read this. The news depends on it.

Did you know each article on Oviedo Community News takes anywhere from 10-15 hours to produce and edit and costs between $325 and $600? Your support makes it possible.

We believe that access to local news is a right, not a privilege, which is why our journalism is free for everyone. But we rely on readers like you to keep this work going. Your contribution keeps us independent and dedicated to our community.

If you believe in the value of local journalism, please make a tax-deductible contribution today or choose a monthly gift to help us plan for the future.

Thank you for supporting Oviedo Community News!

With gratitude,

Megan Stokes, OCN editor-in-chief

Thank you for reading! Before you go...

We are interested about hearing news in our community! Let us know what's happening!

Share a story!